ProfessionalsMembersResourcesDownloadsGuidelinesParasite ID PostersParasite Life CyclesPodcastsTherapiesTick Hosts, Habitats and PreventionFAQsScientificControlEctoparasitesEndoparasitesVector Borne DiseasesZoonosesTravelling Pets

Mites of cats and dogs belong to the subclass Acari and the suborders Mesostigmata, Prostigmata and Astigmata. Mites are, with few exceptions, host specific. Their relevance is from a dermatological standpoint. The following information covers parasitic mites of veterinary importance found on dogs and cats in Europe.

Demodectic Mange Mites

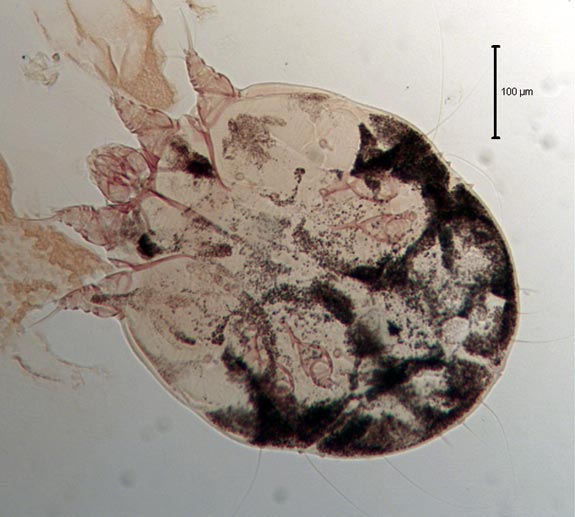

Biology: Demodectic Mange (Demodicosis) in cats and dogs is mainly caused by either Demodex canis, commonly referred to as the follicle mite, or Demodex cati. Female D. canis mites commonly measure up to 0.3 mm long with males measuring up to 0.25 mm. D. cati is slightly longer and more slender than D. canis. In both cases, fusiform-shaped eggs can be found measuring 70-90 x 19-25 μm in size.

Life Cycle: Demodex mites are unable to survive off their hosts. Female mites lay 20-24 eggs that develop through two six-legged larval stages and two eight-legged nymphal stages into eight legged, slender, cigar-shaped adults within approximately 3-4 weeks.

Dogs: There are two types of Canine Demodicosis: Canine Localised Demodicosis (CLD) and Canine Generalised Demodicosis (CGD).

CLD is classed by the American College of Veterinary Dermatology as having up to five lesions. CLD usually occurs with highest incidence in dogs less than 6 months old, but can also be seen in dogs up to 2 years, as one or several small, circumscribed, partially hairless patches, mainly on the face and the forelegs. Most cases of juvenile-onset CLD appear as squamous demodicosis and are characterised by patches of dry alopecia, scaling, erythema, folliculitis and thickening of the skin. Very often the eyelids and a narrow periorbital strip on the dog are affected thus causing a “spectacled” appearance of the lesions. In most cases this form is nonpruritic. CLD can also be seen in adult dogs. CLD is not generally serious and often resolves spontaneously within 6 to 8 weeks without treatment. Relapses are rare because the host has usually regained full immunocompetence.

CGD may occur as juvenile or adult-onset demodicosis. According to classification by the American College of Veterinary Dermatology, the generalised form is present if there are six or more localised lesions, if entire body regions (e.g. the head) are affected, or if it presents as pododemodicosis. Juvenile CGD usually occurs in dogs up to 18 months of age, although this age is not an absolute cut-off. Depending on the underlying condition, it may resolve spontaneously, but in most cases requires treatment, otherwise it may develop into a severe debilitating disease. The adult-onset form of CGD usually occurs in dogs older than 4 years of age and although it can be very severe, it is rare. It usually develops after a massive multiplication of mites and is often a consequence of concurrent debilitating conditions such as hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism, neoplasia, other systemic infectious diseases, or prolonged immunosuppression, which reduce the immune defence mechanisms of the affected animal. CGD may initially present as squamous demodicosis but frequently progresses to severe pustular demodicosis after secondary bacterial invasion of the lesions, which causes deep pyoderma, furunculosis and cellulitis. The skin becomes wrinkled and thickened with many small pustules which are filled with serum, pus or blood; this has resulted in the common name of “red mange” for this form of demodicosis. Affected dogs often have an offensive odour and this form very often develops into a severe, life-threatening disease that requires prolonged treatment.

In both CLD and GLD, if any underlying conditions are present, then these need to be addressed in order to maximise treatment success.

Cats: Demodicosis is a rare disease in cats. It usually occurs as a localised, squamous form with alopecia confined to the eyelids and the periocular region. Sometimes a generalised form will develop, especially if there is an underlying debilitating disease such as diabetes mellitus, FeLV or FIV.

Diagnosis: Demodicosis is diagnosed by microscopic examination of deep skin scrapings from small affected areas of alopecia. Alternatively, in uncooperative dogs, or in sensitive areas where scraping is difficult, hairs may be plucked from an affected area and placed in mineral oil on a slide for microscopic examination. Diagnosis depends on identifying the demodex mites or their eggs.

Treatment: In the case of requiring treatment, amitraz (a member of the formamidine family) and moxidectin (a member of the macrocyclic lactones) are currently registered for the treatment of demodicosis in dogs. There is no registered product for use in cases of demodicosis in cats. Lime sulphur dips have also been reported to be effective. Dips should be performed weekly for 4 to 6 weeks with a 2% solution. Any underlying diseases that could result in demodicosis should be treated as appropriate. Amitraz is registered for dogs only and should not be used in cats due to a high toxicity level.

Sarcoptic Mange Mites

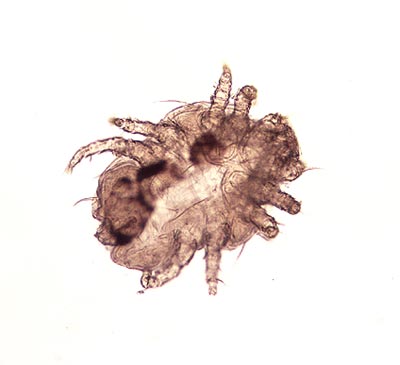

Biology: The genus Sarcoptes contains a single species, Sarcoptes scabiei, which causes sarcoptic mange in a wide range of mammalian hosts, but strains have developed which are largely host-specific with the possibility of temporarily infesting other mammals, which explains the zoonotic transmission from dogs to their owners. The condition is well recognised in both human and veterinary medicine and the human disease is generally referred to as scabies. Sarcoptic mange mites are small, round parasites (up to 0.4 mm in diameter) which spend their entire life cycle on the host, so transmission is mainly through close contact. In general they burrow in the superficial layers of the skin and the lesions thus caused result in mange.

Life Cycle: Sarcoptic mange mites feed superficially on the skin forming small burrows and feeding pockets. Mating usually takes place on the skin surface and the female mite then burrows more deeply in the upper layers of the epidermis feeding on the fluid and debris resulting from tissue damage. In the tunnels and side-tunnels created it lays eggs for a period of several months; these hatch in 3-5 days and most of the six-legged larvae crawl on to the skin surface to continue their development. They in turn burrow into the superficial layers of the skin and hair follicles where they moult through two nymphal stages to become adults. The pre-patent period from egg to adult stage is 2-3 weeks.

Epidemiology: Transmission to new hosts from infested individuals is by direct or indirect contact, most likely by transfer of larvae from the skin surface. S. scabiei var. canis can be highly prevalent in the fox population and can be responsible for a high mortality. Especially in urban areas in the UK, transmission of mites from the fox population to the dog population has been observed. Sarcoptic mange is often seen in stray dogs. It is known that S. scabiei can survive for a few weeks off their hosts, so contaminated bedding or grooming equipment could be a source of infestation. Infestation by host-adapted strains of S. scabiei between different host species usually results in a temporary infestation. Clinical disease in humans after contact with affected dogs is very common.

Clinical signs: The ears, muzzle, elbows and hocks are predilection sites for S. scabiei, but in severe infestations lesions may extend over the entire body. Initial lesions are visible as erythema with papules, which are then followed by crust formation and alopecia. Intense pruritus is characteristic of sarcoptic mange and this can lead to self-inflicted traumatic lesions. Dogs may begin to scratch before lesions become obvious and it has been suggested that the degree of pruritus may be exacerbated by the development of hypersensitivity to mite allergens. Without treatment the disease progresses and lesions spread across the whole skin surface; dogs may become increasingly weak and emaciated.

Diagnosis: Probably the most useful diagnostic feature of canine sarcoptic mange is the intense itching which accompanies the disease; in cases of dermatitis with no itch, sarcoptic mange can be eliminated from the differential diagnosis. The ear edge is the most commonly affected site and when rubbed this elicits a scratch reflex in 90% of dogs. Clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by examination of several, rigorous, superficial skin scrapings for the characteristic mites.

Control: Because of the protected predilection site of the parasites in the skin, its life cycle and the requirement to kill all of the mites to prevent the recurrence of disease, systemic treatments are necessary and proved to be effective. Registered treatments include selamectin and moxidectin in combination with imidacloprid, both as a single treatment repeated after four weeks. Specific treatments should be preceded or accompanied by suitable washes to soften and remove crusts. Sarcoptic mange is highly contagious and affected dogs should be isolated from other animals while undergoing treatment. In multi-dog households and kennels it is advisable to treat all in-contact animals.

Note: Although sarcoptic mange is rare in cats, there have been a few confirmed cases. The clinical signs in such cases are reported to be similar to those of notoedric mange.

Notoedric Mange Mites

Biology: The genus Notoedres closely resembles Sarcoptes both in behaviour and morphology, being a small burrowing parasitic mite which can cause mange. Notoedres cati is the only species of veterinary importance and this occurs mainly in cats; infestation is not readily transferable to other animals but cases have been recorded in dogs, rabbits, hamsters, wild cats and canids. Although infestation with N. cati has been reported from all European countries it is rare in some and tends to be local in distribution in others. Cat notoedric mange is not considered as zoonotic, or only exceptionally and transiently.

Life Cycle:

The life cycle of Notoedres cati is similar to that of S. scabiei in that it is spent entirely on the host and the female mites burrow in the upper layers of the skin creating winding tunnels. Unlike S. scabiei, they tend to aggregate in small groups forming small nests. Eggs deposited in the skin tunnels hatch within a few days and larvae crawl on to the skin surface where they form moulting pockets in which development to nymph and adult stages occur. The adult male seeks a female on the surface or in a moulting pocket. The time taken for development from egg to adult stage is 1-3 weeks.

Epidemiology: Notoedric mange is highly contagious and tends to occur in local outbreaks. Transmission is by close direct or indirect contact, probably by the transfer of larvae or nymphs between hosts. The disease can spread rapidly in groups of cats or kittens.

Clinical Signs: Early signs of infestation are local areas of hair loss and erythema on the edges of the ears and the face. This is followed by greyish-yellow, dry crusting and skin scaling, which progresses to hyperkeratosis with thickening and wrinkling of the skin in severe cases. These clinical signs are accompanied by intense pruritus and scratching, which often results in skin excoriations and secondary bacterial infection. Lesions may spread from the head and neck to other parts of the body when grooming or through simple contact. Untreated animals may become severely debilitated and die.

Diagnosis: This is relatively easy, as there are few other skin diseases of cats which present with intensely pruritic lesions round the head and ears. The small round mites with their characteristic concentric “thumb print” dorsal striations are relatively easy to demonstrate microscopically in skin scrapings. Occasionally humans in contact with affected animals may show a mild dermatitis due to a transient infestation.

Control: There are currently no licensed treatments, but systemic use of macrocyclic lactones (e.g. selamectin) has been used successfully and should be applied as described for sarcoptic mange. Before application of an appropriate acaricide, animals should be washed with an anti-seborrhoeic preparation to soften and remove skin crusts.

Treatment should be repeated until there is a marked clinical improvement and for a minimum of at least 4 weeks. It is important to treat all in-contact animals and replace any contaminated bedding. With early treatment, the prognosis is generally good.

Ear Mites (Otodectic Mange Mites)

Ear mites, Otodectes cynotis, are a cause of aural irritation and discomfort in dogs, cats and ferrets. Infestation may affect one or both ears. Infrequently the mites may cause dermatitis across the body of the animal.

Life Cycle: The entire life cycle is spent on the host, with transfer from animal to animal probably occurring through close contact. Larval ear mites hatch from eggs approximately four days after they are laid by adult female mites. Within approximately three weeks larvae develop through two nymphal stages and eventually to adults. Adult males attach to the second nymphal stage with their suckers, anticipating that the nymph will develop into an adult female. Attachment at the nymphal stage appears essential for egg-laying to occur.

Clinical Signs: Ear mites can occur in any age group of cats or dogs, but are more common in puppies and kittens and more frequent in cats than dogs. O. cynotis are surface dwellers and may be seen as small, motile, white spots in the external ear canal; infestation is typically accompanied by a brown, waxy discharge. Whilst ear mites may be tolerated without clinical signs in some animals, especially cats, there may be a history of pruritus with ear scratching or rubbing and self-inflicted trauma. The pinna and ear canal may be erythematous.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis may be reached by seeing the characteristic brown ear wax similar in consistency to ground coffee, and mites in the external ear canal using an otoscope. Where necessary, samples of wax and debris can be collected from the affected ear canal using a cotton swab or similar. The ear canal may be inflamed and examination and sample collection may be painful for the animal, so care should be taken to have the animal suitably restrained. Ear mites are identified by their long legs, typical of surface mites. The two anterior pairs of legs in all mite stages each end in an unjointed pedicel and sucker.

Control: Ear mites may be treated with local administration of ear drops with acaricidal activity or with a systemic spot-on product containing selamectin or moxidectin in combination with imidacloprid. Depending on the treatment chosen, application may have to be repeated at intervals to eliminate the infestation. In multianimal households and kennels it is advisable to treat all in-contact animals.

Fur Mites (Cheyletiellaby Mites)

Fur Mites, Cheyletiella spp., can infest dogs, cats and rabbits. Whilst infestation may be well tolerated by some individuals, in others it can cause irritation and discomfort. The mites will also feed on humans, causing a localised dermatitis.

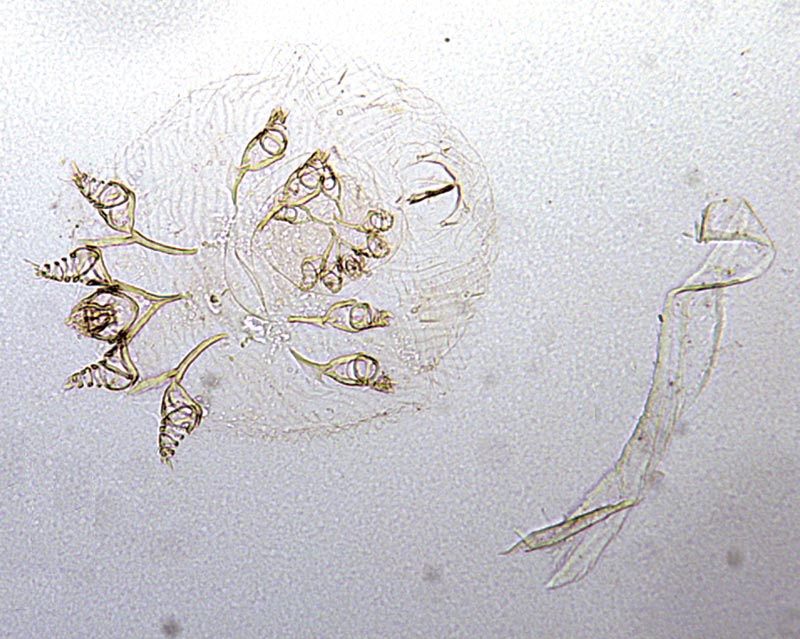

Life Cycle: The entire life cycle takes approximately three weeks and is spent on the host, although female mites can survive for up to ten days in the environment. Adult female mites lay eggs that are attached to the coat. These hatch and develop through two nymphal stages prior to becoming adults. Transfer from host to host occurs readily and rapidly between animals in close contact. Cheyletiellosis is common in kennels; young and weak animals seem to be more susceptible.

Clinical Signs: Dogs and cats are infested with distinct species: Cheyletiella yasguri infesting dogs and Cheyletiella blakei infesting cats. However, these species may not be strictly host-specific. The mites may be well tolerated in some animals with excessive scaling being the only clinical sign, while in other animals pruritus in variable degrees may be present. The large, 0.5 mm mites may be seen as white spots moving amongst the skin scales, hence the term “walking dandruff”. Affected areas may show erythematous and crusting lesions which may appear as miliary dermatitis in cats. Humans may also be infested, particularly around the waist and arms.

Diagnosis: There are several ways of collecting material for microscopic examination to identify mites and thus confirm the diagnosis. Brush or comb the animal’s coat and collect the debris in a petri dish, universal container or paper envelope. Alternatively, apply a Sellotape strip to the affected area and then apply the strip to a microscope slide sticky side down. It is also possible to lightly trim the coat, carry out a superficial skin scrape and collect the debris in a suitable container. After sample collection, the debris may be examined in a petri dish using a stereo microscope (x40 total magnification) and mites may be seen walking amongst the debris. Cheyletiella spp. mites have legs that protrude beyond the periphery of the mite’s hexagonal body, a “waist”, legs with “combs” on the end and palps with powerful claws at the anterior end. Cheyletiella spp. eggs may be seen attached to hairs. Since infected dogs or cats may groom excessively, eggs that have passed through the intestinal tract are sometimes detected on faecal examination.

Control: Infected animals can be treated with a suitable topical acaricide, but there is a general lack of licensed preparations. Studies have shown that topical applications of selamectin, moxidectin or fipronil and systemic administration of milbemycin oxime are highly effective against Cheyletiella. Depending on the duration of activity of any compound, treatment may need to be repeated to eliminate the infestation. Treatment of in-contact animals, particularly of the same species, is recommended, even if they are showing no signs of infestation. Cleaning of the environment, including washing the bedding and vacuum cleaning, helps to eliminate any mites in the environment. Fipronil should not be used to treat fur mites in rabbits due to toxicity risks.

Public Health Considerations:

Owners may be transiently infested after contact with infested animals and develop skin rash.

Harvest Mites (Trombiculid Mites)

There are some mite infestations in dogs and cats that are occur less frequently and are characterised either by their seasonal nature, or by their geographic distribution; these are harvest mites, Neotrombicula (Trombicula) autumnalis, which are responsible for the condition known as trombiculosis.

Life cycle: The adult mites lay their eggs in decomposing vegetable matter and in a few days the eggs hatch into six legged larvae; these are of a characteristic orange colour and about 0.2-0.3 mm in length. Only the larvae are parasitic. In temperate climates, larvae become active in dry, sunny conditions at temperatures exceeding +16°C. This often occurs between July and October; thus the term “harvest mite”. The larvae climb onto the vegetation where they wait for passing hosts. There is no transfer from animal to animal and after attaching themselves to their hosts they feed for several (5-7) days on enzymatically liquefied tissue, epithelial secretions or blood. Thereafter, they detach and continue their development. The subsequent stages (nymphs and adults) live as free-living stages on the ground. To complete the life cycle may take 50-70 days or more. Harvest mites are resistant to adverse climatic conditions and female mites can live for more than 1 year. In areas with temperate climate there is usually one generation per year, but in warmer areas they may complete more than one cycle per year.

Clinical Signs: Cutaneous lesions are usually found in ground-skin contact areas like the head, ears, legs, feet, and ventral areas. The lesions are highly pruritic. Macroscopically they are very peculiar due to the bright orange colour of the larval mites. Severe hypersensitivity reactions have been observed in case of repeated infestation.

Diagnosis: Gross observation of the lesions, together with the time of year and the history of affected dogs and cats having been in the countryside, are often sufficient for a diagnosis. The larval mites can also be seen fairly easily without magnification. Occasionally it may be necessary to confirm harvest mite infestation by taking skin scrapings and where mites are found in the interior of the external ear canal, especially in cats, it is important to differentiate these from Otodectes spp.

Control: Control of trombiculosis is difficult due to the fact that reinfestations are frequent in animals exposed to these mites. Fipronil (in both dogs and cats) and synthetic pyrethroids (exclusively in dogs) can be successfully used to kill the mites, as can other compounds based on organophosphates and/or carbamates. Topical spray treatments may be repeated every 3-5 days in order to prevent reinfestation. Frequent spraying of the commonly affected areas such as paws and ventral abdomen may be more effective than less frequently applied spot-on preparations.