Ticks are temporary blood feeding parasites which spend a variable time on their hosts; in the case of ixodid ticks, each stage feeds for only a short period of one to two weeks. Generally, ticks are of most importance as vectors of bacteria, viruses, protozoa and nematodes, affecting both companion animals and humans. Infections can be transmitted in saliva as the ticks feed or, more rarely, after the tick is accidently ingested.

Both hard (Ixodidae) and soft (Argasidae) ticks occur in the UK but it is the hard ticks that occur on dogs and cats. The ticks most commonly found on pets in the UK are Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes hexagonus and then Ixodes canisuga. Other Ixodes species are only very occasionally seen. Dermacentor reticulatus and Haemaphysalis punctata also are indigenous and found occasionally on pets but only in specific areas. Rhipicephalus sanguineus, a tropical/subtropical tick, might be identified after importation on pets from Continental Europe and elsewhere. All these are 3-host ticks, each stage feeding on a different host, although the 3 hosts could be of the same host species, or the tick may prefer very different host species for each feed.

Species

The ticks most commonly found on dogs and cats in the UK belong to the genus Ixodes (I. ricinus and I. hexagonus are the most common, but I. canisuga and occasionally I. frontalis and I. trianguliceps have been seen). Dermacentor reticulatus and H. punctata and imported R. sanguineus are occasionally found on pets. The habitat of these ticks varies with genus and species from very rural fields and woods, through rural and urban nests/lairs/burrows, to kennels and houses. Ticks are less active in winter although may be encountered all year round. They become more active in the spring and early summer with the potential for activity to be maintained through the rest of the summer depending on climatic conditions. Finally there is a second peak of activity in the Autumn.

- Variously named the castor bean tick, sheep tick or deer tick. Does have preferred host species on which to feed but, despite its names, it will feed on any mammals or birds and lizards.

- Its preferred hosts for the larval and nymphal stages are small animals (rodents then lagomorphs and birds) and for the adults, large animals (particularly sheep and deer on which it has the greatest reproductive success).

- Most common tick feeding on dogs and humans where nymphs and adults in particular are found. The higher frequency on pets compared with other ticks is related to its exophilic habits of searching for a host above ground meaning that passing pets easily become infected.

- Feeds once at each developmental stage and, as the tick often feeds only once a year in the UK, the whole cycle from egg to adult can take three years.

- Requires high humidity (almost saturation) to prevent dehydration on the ground so it tends to be found in wetter areas, particularly in the West and Northern England and Scotland.

- The primary requirement is a thick basal vegetation layer that often occurs where there is poor drainage or poor soil and thick bedrock increases the level of moisture. However, I. ricinus maybe found in woodland even in drier areas such as East Anglia and in some East Anglian and South-Eastern coastal areas.

- Activates in spring/early summer (March to May/June). In hotter areas of the UK tick activity can almost cease during summer, although larvae and nymphs may be active, and ticks remain active in cooler, damp locations. Some ticks become active in the cooler autumn (August to October).

- Can be brought by wild animals to drop off in gardens and parks near its habitats so that ticks and tick-borne diseases have been observed even in suburban gardens.

- Known as the hedgehog tick.

- The second most common tick on dogs and often the most common on cats.

- The larvae occur more or less exclusively on hedgehogs and also other smallish mammals that have nests/dens may become infected (stoats, weasels, ferrets, polecats, foxes, badgers).

- Pets are accidental hosts of mainly adults. As hedgehogs abound in parks and gardens I. hexagonus is common, even in urban areas. Prevalence is greatest in SE England but I. hexagonus is found further north, even in Scotland although at low frequency.

- Activity seems to begin in February and there may be a spring (April/May) peak, a decline in June/July and a second peak in August to October. In the nest there may be some winter activity.

- Known as the British dog or fox tick.

- Cycles primarily in kennels, occasionally catteries, and so is more common on sheepdogs and hunting dogs but also can infect boarding kennels.

- Can be present in large numbers.

- The female can survive a lower humidity and can climb to a considerable height to lay eggs in cracks and crevices of roughly constructed buildings, even in the ceiling of a well-constructed, plastered wall, dog kennel.

- Occurs throughout the UK and Ireland.

- Found on medium to larger mammals that have a burrow or lair, i.e. fox, mink, badgers, so that dogs might acquire single ticks from these habitats.

- Ixodes frontalis, the passerine tick of birds, is found in their nests in bushes, brambles and hedgerows, in woodland, parks and gardens. It occurs particularly in SE England and coastal areas of the west and north. It occurs below nests, under a rookery for example, to infect wild mammals and very occasionally pets. It was first associated with a lethal neurological syndrome in turtle doves in France and since then in association with acute depression and deaths in birds in the UK.

- Ixodes trianguliceps, is the vole (particularly bank) or shrew tick, occurring in their nests and those of other rodents. It is widely distributed in the UK, particularly in wooded areas, and occurs in Ireland and very occasionally is found on pets.

- Variously named the ornate dog tick, ornate cow tick, meadow tick or marsh tick, reflecting its variety of habitats.

- In Europe it is found up to 1,000m above sea level on grasslands, pastures, fringes of meadows, and grassy paths in woodlands, along rivers and streams, banks of ponds, in marshy areas and peat bogs. It has been described in the sand dune systems and coastal pastures of West Wales and South-West England, particularly North Devon. It has recently been found in coastal South-East Essex presumed transported by sheep moved from Wales and would seem to be spreading in the UK and in Europe.

- The life cycle can take place in 1-2 years with most activity described March to June and August to November.

- It is found on domestic and wild animals, cattle, sheep, dog, fox, hare, hedgehog. It is mainly the adults that feed on the larger animals while the larvae and nymphs feed on burrowing and ground dwelling small mammals.

- Has been described in the marshlands of Kent and Essex but now has been reported in West Hampshire.

- It was common on sheep on the North Wales coast.

- It feeds on both birds and mammals with a life cycle taking 2-3 years and spring and autumn activity.

- Known as the brown dog tick, will utilise species such as cats, foxes and cattle as hosts but the dog is its preferred host.

- It is a tropical/subtropical tick, but can survive in temperate climates (central and northern Europe) when protected within domestic environments such as homes and kennels.

- It can reach high numbers in southern Europe with activity mainly between March and October.

- Although not indigenous to the UK it has been identified on occasion on pets and in kennels and dwellings after import from mainland Europe and elsewhere and is a risk to pets being taken abroad.

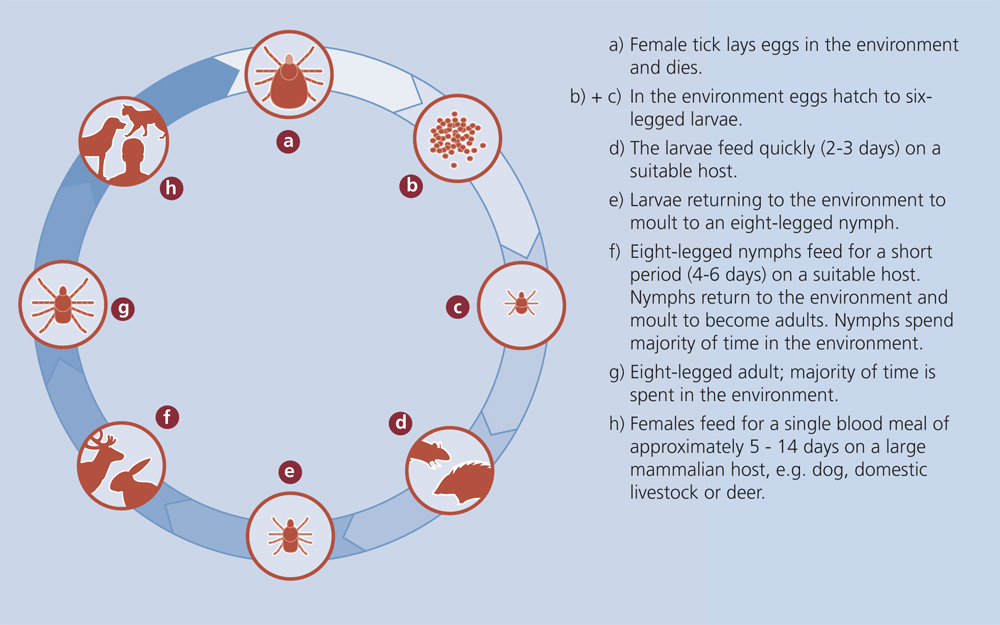

Life Cycle

- Ixodes ricinus, D. reticulatus and H. punctata are exophilic ticks living on top of the ground, albeit in humid undergrowth. Their eggs hatch producing 6-legged larvae.

- The larvae climb onto grass to wait for (quest) and ambush a passing host that they attach to and take a blood meal. After feeding for 3-5 days they drop off the host, digest the blood and moult (shed their skin) developing into the next growth stage, an 8-legged nymph.

- The nymph also quests for a host from which it feeds for 5-8 days before dropping off to moult into an adult.

- Mating on or off a host, the female then takes a final and large blood meal over 7-14 days from a third host. After this she drops off the host to digest the blood and lay her eggs.

Clinical signs

- Ticks can be found all over the body but the main predilection sites are the non-hairy and thin-skinned areas such as the face, ears, axillae, interdigital, inguinal and perianal regions.

- Removal of blood, in heavy infestations and under certain circumstances, may lead to anaemia.

- The wound caused by the tick bite may become infected or a micro abscess may develop as a reaction to the mouthparts if the tick is forcibly removed and the mouthparts remain embedded in the skin.

- Attached engorging females ticks, which can measure 1cm in length, are easy to see.

- Clinical signs relating to the diseases transmitted by ticks may be seen, either whilst there is still evidence of tick infestation or subsequently. The main importance of ticks is their role as vectors of pathogenic agents which cause a range of tick-borne diseases (TBDs). Some pathogens can be transmitted between different tick generations and/or life cycle stages, and some may thus be transmitted by every life cycle stage during feeding. Salivary fluid is the main route for pathogen transmission. Babesia spp., Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Hepatozoon canis, Acanthocheilonema (Dipetalonema) spp., Bartonella spp., Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma phagocytophilum, A. platys, Rickettsia spp., flaviviruses and others can all be transmitted by ticks. Individual ticks may harbour more than one pathogen often leading to clinical syndromes atypical of a single disease.

Treatment and Control

Visible ticks should be removed as soon as possible after the ticks are seen to avoid the possible transmission of many of the TBDs (see VBDs section of this website). There is a large variety of purpose-designed tick removal tools available; these may be used for removal of ticks attached to the skin (oil, alcohol or ether should not be used!). Gloves should be worn. Careful disposal of removed ticks is required, so that there is no opportunity for them to move to another host.

After diagnosis of a tick infestation, it may be advisable to apply an acaricide, because not all of the ticks, especially the larval and nymphal stages and unengorged adults may be detected on the animal. The possibility that other pathogens had been transmitted must also be considered.

Generally, after diagnosis of a tick infestation, tick prophylaxis should be instituted for the remaining tick season for the individual and all associated animals.

Prevention and ongoing control

Tick prophylaxis should cover the entire period during which ticks are active. Depending on the level of risk this may consist of regularly checking pets for ticks and/or acaricidal treatment.

To advise pet owners and achieve owner compliance, the duration of efficacy for an individual product should be established from the relevant product data sheet so that the owners can be advised of the correct retreatment intervals.

It is advisable that animals are checked regularly, in particular towards the end of the protection period to ensure that any visible ticks are removed and early repeat treatment considered if appropriate. It should also be remembered that the duration of efficacy may differ between tick species, again highlighting the importance of visual checking to verify that the treatment remains effective.

Steps to avoid tick infestation and reduce TBD risk:

- Avoid or limit access to areas of known high tick density or at times of the year when ticks are known to be most active.

- Inspect animals for ticks daily and remove any ticks found.

- Use acaricides with a residual action and water resistance.

- Cats appear to be less affected by TBDs than dogs. Where ticks are a problem on cats then they should be controlled with a suitable acaricide. WARNING: highly concentrated synthetic pyrethroids or amidines (if registered for dogs only) are toxic for cats.

Scenarios

- Minimal infestation risk (e.g. animals with restricted or no outdoor access):

Regular visual examination and, if ticks are found, manual removal. In the case where ticks have been found and removed, a follow up application of an acaricide may be advisable to ensure all ticks are killed.

- Regular infestation risk (e.g. animals with regular outdoor access and undefined risk of reinfestation):

Regular treatments according to product label recommendations to achieve constant protection at least during the "tick season" in areas of Europe with clear cold winters. For warmer areas or where ticks may survive in houses or in shelters, e.g. R. sanguineus, treatments may be necessary throughout the year.

- Reinfestation risk (e.g. shelters, breeders premises):

Regular treatments according to product label recommendations to achieve constant protection should be carried out throughout the year.

- High risk of TBD transmission:

In areas with a high prevalence of TBDs, pet animals are at risk of acquiring these diseases. Regular treatments according to product label recommendations to achieve constant protection should be carried out throughout the year. Acaricides with additional repellent activity have an immediate effect and prevent ticks from biting thus reducing the chance of acquiring TBDs. However it has also been demonstrated that other acaricides can be successful in the prevention of TBDs, especially those that are transmitted late in feeding.

- Kennel or household infestation:

Regular acaricidal treatment of pet animals coupled with environmental treatment using a compound from a different chemical group, can be used where an infestation with R. sanguineus or I. canisuga has established within a kennel or household environment.

Back to Ectoparasites

| Title | Size | |

| 0.28MB |  |